The Spectrum of Project Based Learning

Defining PBL so that every teacher and student can thrive

The issues that surround Project Based Learning (PBL) mirror the education system as a whole: no agreement upon the definition of terms and a lack of support in implementing a good idea. There seems to be nearly endless variations of what defines project-based learning. Is there a gold standard of PBL if no teacher can execute that standard on a consistent basis? What is the best duration of projects? How often should we run projects? And how do we connect them to the learning objectives? Teachers need more support in both the definition and implementation of PBL.

Over the last twelve years I taught 32 different classes that required significant variations in how I implemented PBL in my classrooms. Early in my career I taught Earth Science and AP Physics with some PBL sprinkled in. At the same time, I was introduced to Project Lead the Way, a curriculum provider that offers schools a rich engineering PBL curriculum. I initially stuck with lectures and thought the projects were a nice to have, but quickly realized it was the projects that drove the learning more than my lectures1. Later in my career I pushed PBL to the max by creating a course called Social Entrepreneurship, Engineering, and Design (SEED), where 80 students worked on four big projects throughout the year. During each project students would collaborate in teams of 8 students and build a solution that consisted of the entire design and business creation lifecycle.

After running such a wide variety of classroom structures, I realized that PBL hasn’t lived up to the research because it is often defined as a binary. Teachers and schools often say we do PBL, or we don’t do PBL. This false choice makes it so that schools and teachers limit their experimentation with PBL. The lack of experimentation means that tools and the practice of PBL doesn’t grow, spread, and evolve like any practice needs to in order to be successful.

The only way we can help PBL spread and evolve is by redefining it as a spectrum that every teacher and classroom exists upon. My hypothesis: Every school and every teacher use some sort of PBL already. Maybe it’s just a small project that students work through in a single class period, resulting in an exit slip on a Post-it note. Or maybe it’s a semester-long project where students are producing novel research. Those two sides of the PBL spectrum help us define the two key factors to measure the PBL spectrum, frequency of projects and the vector properties of projects.

A vector, while also a great villain, is a math object with both magnitude and direction. The vector properties of a classroom project are its duration (time length = magnitude), and the direction it guides students. Every project starts with a learning objective but can point students in a wide variety of directions.

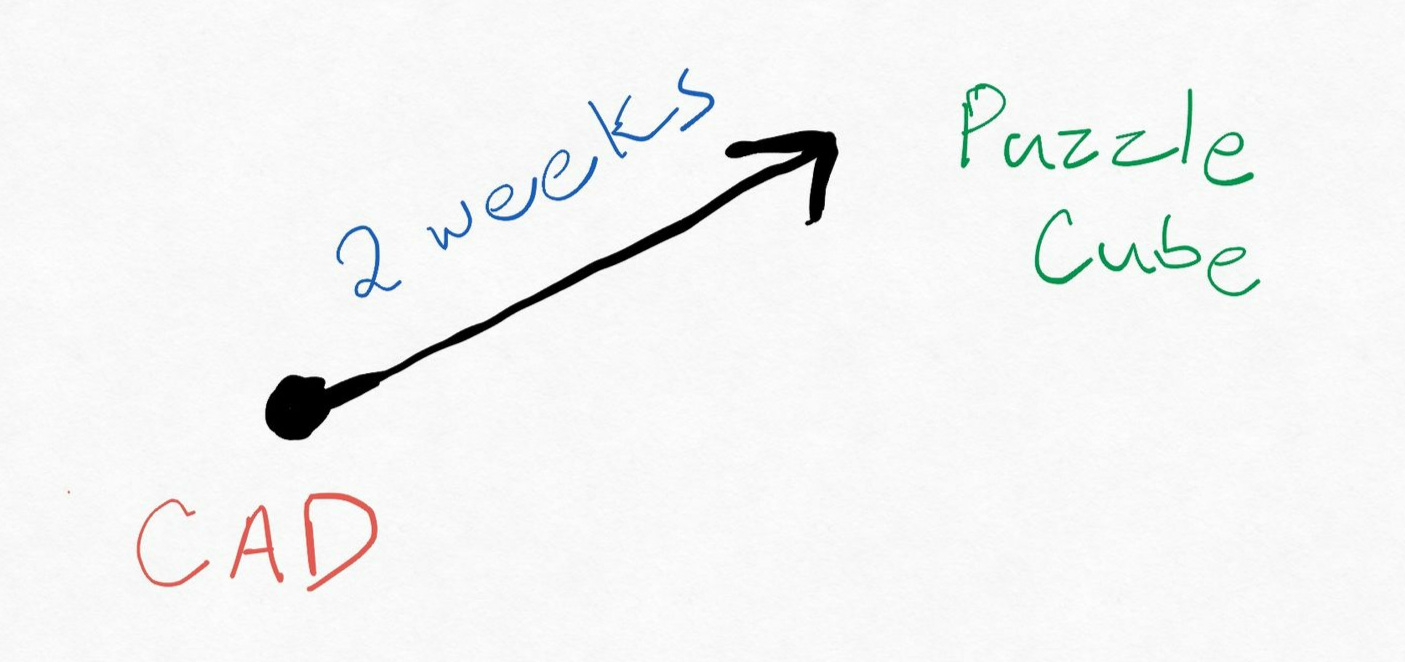

An example of this vector in my Computer Integrated Manufacturing class was to start with the learning objective to communicate an idea using Computer Aided Design (CAD) software. I had my students spend 2-weeks developing and applying this skill, and I could have them create a puzzle cube.

Most classes limit the directions a project can point students in. This has been the only way to make PBL manageable. This past year I realized that Project Leo can support teachers and students in executing projects that stem from the same learning objective and lead students in a variety of directions that they care about.

The next key feature of PBL is the frequency of projects. A common misconception is that PBL has to be an entire unit, or even an entire semester long. The longer a project runs, the harder it is for students to stay focused and for teachers to manage. Keeping students on task and motivated to pursue one project for one semester takes a ton of planning, the ability to break down and manage tasks, and the ability to pivot. A teacher new to PBL who tries to take on this more advanced style of PBL implementation without much support is bound to fail. I felt that pain when I took on a semester long project early in my teaching career without realizing how quickly student lose their motivation to pursue a long duration project.

The key is for teachers to experiment with the duration that allows them to do two things. First, they need the time to develop the skills necessary for the target learning objective. Second, they need to give their students the time to apply those skills. Every learning objective will have a different recommended time horizon. Teachers and students will also feel comfortable with varying lengths of time for projects. The length of time of each project will determine the possible frequency of projects throughout a class.

An analogy in physics can help clarify this relationship. The most well-known spectrum is the electromagnetic spectrum defined by the wavelength and/or frequency of the electromagnetic wave. The longer wavelength and shorter frequency are radio waves. The shorter wavelength and higher frequency are gamma radiation and x-rays.

Instead of wavelength, we have duration of a project. That duration will then determine the frequency of projects in a class.

When we combine the vector properties with the frequency of projects run in a particular classroom, we can finally define where a teacher and class lie on the spectrum of PBL. The x-axis on the PBL spectrum becomes number of successful student projects run during a school year that are aligned with learning objectives of the class.

Combine that alignment with the Ikigai of every student, and the classroom becomes an engaging community that can finally support this anxious generation.

As of today, the tools to support teachers and students to move along the spectrum of PBL don’t exist. Grant Sanderson suggests that not only are the vector properties of our projects important, but we must consider the forces from the world that are pushing on those vectors. Our team at Project Leo loves to analyze these forces and build the tools that every teacher and school deserves. If you want to try out the tools we have built, reach out to us today.

The original version carelessly referred to PLTW as lecture heavy. I was referring to my implementation, not the curriculum itself.